Event Summary

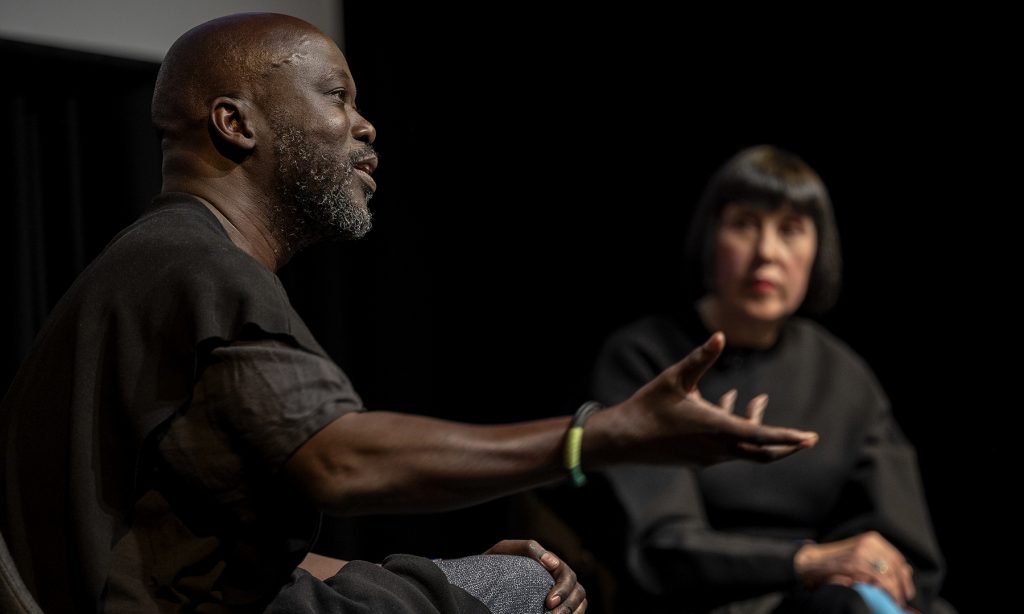

This week at JW3, architectural visionary and founder of Adjaye Associates, Sir David Adjaye OBE, sat down with award-winning design critic and author, Alice Rawsthorn OBE, to discuss three of his culturally responsive global projects, and their mutual passion to physically build a brighter future.

Despite not knowing he wanted to be an architect, specifically, from a young age, Adjaye showed an interest in thinking creatively and enjoyed drawing, making up scenarios, and creating characters. He credits his art teacher at school, whom he still knows to this day, for noticing his affinity for three-dimensional thinking and encouraging him to do an architectural foundation course, during which he “fell in love” with architecture.

As one of the very few Black architects coming to the fore in Britain at the time, Adjaye describes professionally entering architecture as “brutal but inspiring”. In a post-recession era of cultural renaissance, he witnessed a shift in traditional architectural patronage and saw his early career being supported by the phenomena of the YBA movement and peers in the art world, in the form of houses and small cultural projects.

In this conversation, Alice Rawsthorn, author of ‘Hello World: Where Design Meets Life’, was keen to discuss three of Adjaye’s current projects that are linked by their respective associations with faith; the first being the UK Holocaust Memorial & Learning Centre in London, a commission won by Adjaye Associates following an international competition.

Adjaye wanted this project to show “the British lens on the Holocaust experience.”

As the last country in Europe to make a Holocaust Memorial, Adjaye wanted this project to show “the British lens on the Holocaust experience”. He interpreted the brief as an opportunity to create a dignified civic and national space of mourning, with a particular ambition for it to serve as an archive for the remaining survivors.

After entering one of the 21 gate chambers, in which the viewer is encouraged to reflect on their experience of being detached from their exterior support network, one is led into a commemorative chamber before entering the educational Learning Centre. The memorial’s proximity to the Burghers of Calais, the Monument to Slavery, and the Emmeline Pankhurst Memorial extends the narrative of horrors experienced by those before us and encourages the viewer to question the role of society and its institutions in establishing human welfare. Not without its administrative complexities, the commission has become a legal matter on which Adjaye hopefully awaits the adjudication.

Turning to discuss another of Adjaye’s current projects, the Abrahamic Family House in Abu Dhabi, Rawsthorn reminds us that this is not only the result of another international competition, but one with faith, or multiple faiths in this case, at its core. The idea of the project was to understand and convey the three key religions connected through Abraham – the location being key here in that it’s the only place where the ruler allowed a synagogue, a church, and a mosque to be built at the same time. Adjaye credits his firm being rewarded the commission by identifying that since architecture has a history of being complicit in separating religions diametrically, here lies an opportunity to use architecture to be complicit in showing unity between faiths. Whilst each religion has its own physical space, Adjaye tells us it is the garden that serves as a powerful metaphor for community.

“Here lies an opportunity to use architecture to be complicit in showing unity between faiths”

Rawsthorn concludes her conversation on faith in architecture with Adjaye by discussing the National Cathedral of Ghana in Accra. As a result of the (predominantly) West African Christianity splintering off into many groups, Adjaye saw that it would be beneficial to bring these groups together and to create a dialogue between them that ensured growth and community amongst them. Being the first Cathedral for Christians in Ghana, this commission was required to provide both a high-function and sacred space in which people from all faiths could gather for religious ceremonies, mourn national heroes, and celebrate symbolic festivals – the multi-use space can host over 20,000 people on the podium whilst the hall within can hold up to 5,000. As the son of Ghanaian-born parents, but having never lived there himself, Adjaye describes this project as a “calling” and a trigger for his return there with his family. Furthermore, Adjaye’s vision for the National Cathedral of Ghana has been heavily influenced by his extensive travel across every country on the continent, during which he wrote a book, ‘Adjaye. Africa. Architecture.’

“I hate the word sustainability”

Encouraged by Rawsthorn to discuss his priorities for the future and his ecological responsibilities, Adjaye says, “I hate the word sustainability”, and reiterates that the backbone of each of his projects involves adaptive reuse, lightweight construction, low carbon concrete, and locally sourced materials. “It’s part of the DNA of how we’ve always thought,” he says, and the only way to practice architecture, which is the most consumptive thing on the planet, as an art form.

Event Videos

Event Photographs

Featuring

Alice Rawsthorn

Alice Rawsthorn is an award-winning design critic and author, whose books include Design as an Attitude, Hello World: Where Design Meets Life and, most recently, Design Emergency: Building a Better Future.

Sir David Adjaye

Sir David Adjaye OBE is a Ghanaian-British architect who has received international acclaim for his impact on the field.